Afghanistan in Three Voices

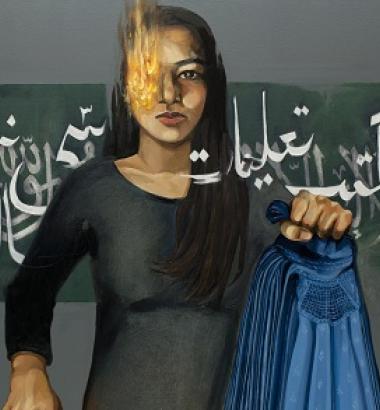

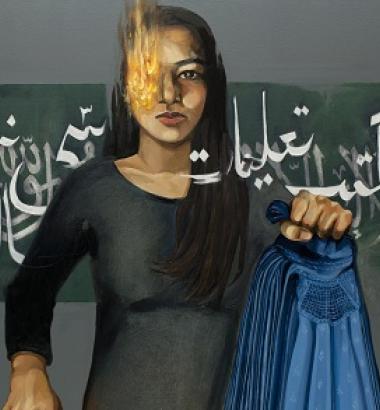

Three Afghan women write about violence and shelter, the Taliban, and getting to vote.

Three Afghan women write about violence and shelter, the Taliban, and getting to vote.

It’s one thing to theorize about the transition to democracy, another to live it. Here, three Afghan women, Norwan, Mariam, and Nasima, describe life in a country that, after 30 years of war, has vowed to become more liberal.

They all know refugee life, as part of an immense Afghan diaspora that grew following the 1979 Soviet invasion (in the 1980s, one of every two refugees in the world was Afghan), the 1996 Taliban takeover, and the U.S.-led invasion in 2001. The chaos kept school out of reach for many children, especially girls. Today, Afghanistan has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world, at 43 percent for males and less than 13 percent for females. A recent survey by TrustLaw, a legal news service, named Afghanistan the most dangerous country in the world for women. In becoming educated women who could write their own stories, Norwan, Mariam, and Nasima really have all but walked uphill both ways to school.

The three women contribute regularly to the Afghan Women’s Writing Project, an online workshop and magazine that publishes several dozen writers, and where, as a volunteer editor, I first encountered their work. Animated with anger, hope, and sweet humor, the poems and essays tell the story of a people who will never reconcile themselves to tents and funerals. Children, families, friendships—they’re all important, but the writers refuse to be confined only to domestic concerns. Facing the looming withdrawal of U.S. combat troops next year and the prospect of peace negotiations with the Taliban, the writers were eager to talk about the future of democracy in their homeland.

While they’ve written here in English, it is not, of course, their first language, nor even their second—among the other languages they speak are Dari, Pashto, and Urdu. For their own security, they use only their first names, and have omitted identifying details. –Darcy Courteau

A Way of Good Thinking

In the cold winter nights when I was a child and my father talked about the meaning of freedom and democracy, I could not really understand those words, even though I thought they were the names of my dreams.

Then the Taliban took power when I was 15 years old. Six years after that, democracy came together with B-52 bombers following 9/11. We had a small, old radio running on dying batteries, and we listened to the news. That is how I learned about the war against terrorism.

I’d grown up in war and had heard rockets and bombs. When the Mujahedeen were fighting in Kabul, I understood which kind of rockets they shot, but the bombs from the United States’ B-52s made sounds that I still can’t forget, as if the mountains above had become angry and suddenly crashed down. Sometimes I went deaf for hours and could not hear anything. For the first time I experienced the fear of being dead. When one of the bombs blasted very close to our house, I cried and hugged my father and looked at his eyes. He told me that the war would be over and we would experience freedom soon.

I told myself to wait for the end of the war, and for the day to come that I could go to school. At that time nothing was important for me but to be out of the blue cage, my stupid burqa, and to go to school.

I heartily welcomed democracy. With it I changed from an uneducated Afghan girl to a proud, educated woman—a golden achievement. After six years of being locked in the house, I could go to school with a pen and paper in my school bag. At school, however, some of my teachers said that democracy is a bad word, and that anybody who likes democracy is against Allah. In my class I learned that democracy is not for Afghans; it only belongs to Western people.

At that time, everybody had a special definition for democracy. A woman imprisoned for killing her husband said that she killed him because he was not a good man, and she could do it because now we had democracy in Afghanistan.

Other women understood they had civil rights. Women who had been forced into marriages, having their first child at age 13—some did not want their daughters to be child brides, too, and started to fight against oppression. Other women ended their lives by burning themselves. Now that they knew their rights, they could not tolerate the wrong decisions of men in their family. In Kabul, I went to the hospital to talk with burned girls and women. They all told me they did it because there was no other option to release them from their family’s decision to stop their education, or force them into arranged marriage.

Other families showed that if they could not make big changes, at least they could say no to barbarism. Some families that were not educated sent their daughters to schools, even in unsecured and remote provinces such as Kandahar, Paktiya, Logar, Bamyan, and Badghis. Families believed that we needed educated women, especially women doctors. Even old women could go to literacy courses and get a job outside the house. And now, Afghan women could join the military.

A good telecommunications system meant that people from a shopkeeper to a help man with his donkey could own a mobile phone. Telephone companies held midnight specials, and young boys called their girlfriends secretly and could not sleep until morning. (I pity this misuse of the energy of our young generation.)

We had freedom of speech. Anyone could own a radio station or TV channel. We had about 10 TV channels that all broadcasted dance clips and music. Most of the young boys and girls wanted to be singers! Ariana Sayed and Muzhda Jamalzada, who’d fled the country as children and became pop stars abroad, returned to give concerts.

I got to vote in the second parliamentary election, in September 2010. My father had died by then, and none of my family members had decided whether or not to vote. If they did not, then I didn’t have permission to go out on Election Day. It was almost the end of the day when my brother came and told my mom and me, “We are going to vote!”

In the car my brother said that both of us should vote for Mullah Abdul Salam Rocketi, a warlord during the Mujahedeen time who had killed a lot of innocent Afghans. My brother supported him because Rocketi was paying $100 to each person who voted for him. I was shocked, and thought that it is better to commit suicide than vote for Rocketi. My brother gave us a camera so that we could take a picture of our ballots to show we’d voted for the right person. When I went to the polling station and mom took the camera, my hands were shaking as if somebody stood beside me with a knife. I selected my favorite person who I thought could do something for Afghans.

But my hope for having a democratic country was like a paper boat in the water.

Now I feel ashamed of myself when I remember that when the world introduced Hamid Karzai as president of Afghanistan, and the U.S. government and international community hugged him and kissed him, while watching him on TV I was clapping for him and welcomed him with tears.

We trusted Karzai and thought that because he was selected by the international community, we would experience big changes. The world paid special attention to the situation in Afghanistan, and money rained down from everywhere. But it went to Karzai and his family, his corrupt, lazy cabinet, and people around him. Throwing away their turbans and wearing ties and suits, they were very successful in pretending to support democracy while they filled their pockets with money. The international community would give money to build highways, for example, but because in Afghanistan there is no transparency, a contractor would keep the money and use mud for the roads instead of concrete.

Afghans were disappointed in Karzai’s misgovernment, and some thought that the Taliban would be better. Now, when people have problems with corrupt courts, some turn to the Taliban and ask them to help solve their most important issues.

The past 12 years have not brought changes to the lives of poor, ordinary Afghans. Women still suffer violence at home. Children as young as seven are in the streets begging, and they are the supporters of the house.

We had presidential and parliamentary elections again, and all went well according to media announcements. The Afghan people selected a president for themselves, Afghanistan had a parliament, and, by the way, again the world congratulated our failures!

But it was not only Afghanistan’s government that did not understand the meaning of democracy. Some people really considered it a bad word, while they expected the United States and other countries to rebuild Afghanistan! Many Afghan people really counted on Obama to bring democracy and stability to Afghanistan. But with the bombing of women and children in the villages, and then, worst of all, talking about making peace with the Taliban, the U.S. government showed that their efforts to bring democracy to Afghanistan were a commercial—it looks so attractive in the newspaper, but if we go and buy it, it isn’t worth a penny. It is still a puzzle for Afghans that the United States is thinking about making peace with the Taliban. I feel pity for those Americans who paid the high cost of losing their lives in 9/11, for American soldiers who died in Afghanistan’s war, and for Afghans who died in wars against the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Making peace with the Taliban means that, yes, we forgive you! And who can guarantee that Afghanistan will not become a nest of terrorists that will bring up other bin Ladens?

Democracy is a way of thinking, good thinking. It doesn’t mean that whatever your heart wants to do, do it. I think that democracy cannot go together with war. As long as we Afghan people ourselves don’t work for real change and freedom, and as long as we put the Quran in the high shelves of our houses and instead respect ignorant mullahs as leaders, we can never experience democracy in Afghanistan. –Norwan

Why Am I Remembering Sad Stories?

I was a teacher in a primary school, with a university degree, when the Taliban captured Afghanistan in 1996. The Taliban did not allow women to go outside their homes unless they were sick, and then they were not allowed to go alone to see a doctor. Outside, they had to wear burqas. But one day I went out without wearing one. I had to accompany my mother-in-law to a doctor’s appointment, and my family owned just one burqa. I covered my body with a big shawl and I covered my face. At a crossroads, we ran into some members of the Taliban. I looked away with my eyes, but the Taliban began beating me. There was no law to defend my rights as an Afghan woman. I thought that there was not any other choice for me but to leave my country.

I migrated to Pakistan with my husband, three sons, and my daughter (I now have two more children, a daughter, eight years old, born in Pakistan, and a son, two years old).Most Afghan refugees in Pakistan made carpets, and they had to work very hard for 16 hours a dayto make rent money, and to cover their huge daily expenses. They could not afford to send their children to school. I decided to work as a servant in a Pakistani house to earn money for my children to go to school rather than weave carpets. But every day when I started to sweep the Pakistani house, I started to cry. I not only felt my life’s pain—I felt all of our homeland’s hardships. Finally, I was able to start a school for immigrant children with funds from the International Rescue Committee, and I established some classes for young girls and women.

After the United Nations and United States helped create an Islamic republic in Afghanistan, we returned to our country. I started a job in a different nongovernmental organization that helps provide opportunities for rural women in order to raise their income and their awareness about their role and rights. Women have the right to education, work, and legal support. According to Afghanistan’s constitution, every citizen who is at least 18 years old, male or female, has the right to vote. We are evidence of a big change.

Today, women can go everywhere, with permission from family. As an Afghan woman, I have the permission of my husband to go alone outside of our country to attend events and programs related to my job. We are in a Muslim country, and it is a basic requirement of our religion to get this permission. I am very happy with my rights. Currently, I am very happy with my life and my job.

But even while I talk about democracy, I think of all the crimes that I hear about on the news every day. For example, there was 15-year-old Sahar Gul, rescued from the home of her in-laws after being tortured for months. She had refused to be forced into prostitution. And there are thousands of similar stories of Afghan women and girls, gloomy tales. But why I am remembering such sad stories while I am talking of democracy and freedom?

Some of our people face problems because of security issues. Many of our problems are caused by ignorance, misconceptions, and illiteracy. In city centers the problems are fewer, but in remote areas there are a huge number of violent attacks against women. My concern is that the Taliban will destroy our security and deprive women of their rights. I think we need to work more through various programs and projects to provide awareness about law.

We tolerated a lot of problems caused by decades of war in our country. Today there are gains in education, construction, and civil rights, especially women’s. There are scholarship opportunities, employment opportunities, and so on. I don’t want the United Nations or the U.S. Army to leave Afghanistan after 2014. Please provide support for Afghanistan in the upcoming election and for the establishment of a good policy to bring peace and democracy in our country. –Mariam

A Message of Peace

I was born in a refugee camp in Iran, but my family had a bad time as immigrants there, so in June 2001 my father decided to move us back to our country, Afghanistan. He said that we should destroy all of our photos, books, mementos, notes, and music CDs, because the Taliban don’t let people have these things. He warned us that women must have burqas for hiding their faces, and being a woman means not having rights to make choices or go to school, or to have rights of expression. We just had the right to listen to men and do what they wanted us to do.

It was very hard for me to accept these laws because at that time I was a 16-year-old and had so many wishes as a woman. I wanted to continue my education and travel to other countries to learn about different cultures.

When we put feet to our country’s ground, instead of there being leaves and fruits on trees, there were pieces of cassette tapes and CDs. There were rough men with soiled faces, high turbans, long beards, and guns full of bullets. They were Taliban soldiers.

Everywhere was dirt and dust. There was no sign of peace or friendship or prosperity. War was hungry and thirsty children sitting on the streets to beg rather than going to school.

We arrived in our city. Frightened people ran toward us to watch; they knew that we had come back from living in Iran. They were good people, and their wish was that we would be OK. Their hearts burned to us; their faces told us, “God will save you from this situation.”

Four months later, we heard on the radio news that the tyrants had been pushed out. It was a free country. Children could go to school, and both men and women could go to jobs according to their experience and education. Even the sky knew that this country needed rain, and it poured that night. This rain was the sign and message of peace and friendship and for the people of Afghanistan to flourish.

I married in 2003 and became a teacher, and when the government had an election for president the next year, I got a voting card. I saw an old woman, about 90 years old, crying from delight. She said, “My God, I arrived to my wishes!” and kissed her voting card.

The promised day arrived. I wanted to go to the voting site; it was my school where I was a teacher. But I faced some problems from my husband. He was a fan of Yunus Qanooni, one of the candidates. I didn’t like Qanooni, but so I could participate in the voting process, I lied to my husband and said, “Fine and OK, I will vote for Yunus Qanooni.” Five minutes before the polls closed, I was the last person to vote. I got a pen and with pleasure voted for Hamid Karzai, and I was so happy for completing my duty as one human, an Afghan woman.

Now I am divorced, and I am living with my mother and my young son, whose name means “my hope and wishes.” Sometimes I feel like my ex-husband is a shadow in back of me, and I feel like he wants to kill me or beat me again. I always try to travel by car, not as a pedestrian, because I am afraid. Most painful for me is when I think he will come and take my son away.

Now I am not a teacher. I work for an organization that supports fair elections. Elections face serious challenges. If we don’t pay attention to them, we will endanger the achievements of 12 years. Lack of security, lack of awareness among people in villages, and election rigging are all problems.

What I see in Afghanistan is not true democracy. The Islamic republic countries cannot accept components of democracy; for example, there is not freedom of opinion and expression. The culture of the people cannot understand it, because a lot of people speaking on the radio and TV are against the government or public authority or are fans of one person of one political group based on ethnic prejudice.

Democracy can be realized in a society where people have knowledge about the word “democracy,” and people have experienced peace in the country for several years. But years of war in Afghanistan have caused a backward mentality in people. Now it is not that easy for people to accept democracy.

Finally, I want to share with you some of my search for the meaning of democracy:

If I asked some children, “What is democracy?” they would answer me: “To follow the ball and kite, to play and build snowmen in winter and wait for the coming of spring.”

If I asked a farmer, he would say: “To plow land in the spring and harvest in the summer andhave a slice of bread in winter.”

If I asked a woman, she would say: “Having life without violence.”

If I asked a mother, she would say: “To foster children and give them kindness.”

If I asked a shoemaker on our street, he would say: “For a moment I can warm my frozen hands in winter.”

If I asked street children, they would say: “Going to school to be a doctor or engineer or manager.”

If I asked students in schools: “To turn the pages of books and color on our hands with pens.”

If I asked some birds: “Soaring in the sky and not in a cage.”

Fishes of seas: “Clean seawater.”

The blind: “To see the light of day and sun, and not always see the dark of night.”

The deaf: “Hearing the beating of mother’s heart and the sound of friends.”

If asked a patriot, the patriot would say: “I love my beautiful country, and I want to fall in it and feel the roses and smell the plains and mountains, not the reek of war and blood.”

–Nasima