Infinite Rest

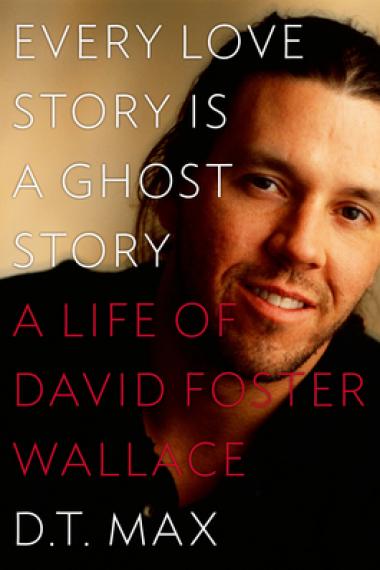

EVERY LOVE STORY IS A GHOST STORY:

A Life of David Foster Wallace.

By D. T. Max.

Viking. 356 pp. $27.95

EVERY LOVE STORY IS A GHOST STORY:

A Life of David Foster Wallace.

By D. T. Max.

Viking. 356 pp. $27.95

In 2008, David Foster Wallace hanged himself at his home in California. He had emerged on the literary scene in 1987 with his first novel, Broom of the System, but is probably best known for Infinite Jest, published nine years later. The famously hefty novel, with its hundreds of endnotes, rendered America’s relationship with its appetites in an original voice—a new language that was sprawling and obsessive in a way that suited its subject. By the time Wallace died, he had also published three short-story collections, two collections of essays, and a book-length pop-science essay on infinity. Last year, his longtime publisher released The Pale King, the novel he was working on when he died. Wallace accumulated detractors as well as fanboys, but few neglected to acknowledge his outsize talent and uncommon intellect. His impact was such that only four years after his death, we have a biography on our hands—New Yorker staff writer D. T. Max’s Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story.

Biographies this contemporary with their subject are most often written about celebrities, and to the extent Wallace might be classified as one, Every Love Story fills a similar demand. Inquiring minds are nothing new, but for all the appetites Wallace wrangled into Infinite Jest, our collective jones for information has truly come into its own since the novel’s publication 16 years ago, sharpened by unprecedented access to data. While Max’s biography may owe its magazine pacing and early arrival to this dynamic, it is nonetheless the first to step into the very real void left by Wallace’s sudden and voluntary departure at the age of 46—a loss that is still hard to measure, of a writer doing the important work of mapping out a landscape that was familiar and yet had somehow gone uncharted.

An artist’s biographer must attempt to identify the underpinnings of art in life, and Max obliges, exploring Wallace’s intellectual evolution and literary influences, employing a good deal of correspondence with fellow luminaries and forebears—letters to Jonathan Franzen and Don DeLillo, whose responses are often conspicuously absent—and documenting the struggles with depression that affected most of Wallace’s adult life. The effect of Wallace’s life on his art is palpable, particularly in his unsettlingly acute portraits of depression in the short stories “The Depressed Person” and “Good Old Neon,” the latter of which depicts the recursive mental patterns of a narrator who will ultimately commit suicide.

Some of the connections Max so matter-of-factly states, however, are lacking in nuance. Of Wallace’s time at a recovery house, he writes, “Wallace created dozens of characters, many capturing aspects of how he saw himself.” The character Joelle Van Dyne in Infinite Jest is a stand-in for writer Mary Karr, the target of Wallace’s real-life infatuation. And Max homes in on Wallace’s fraught relationship with his mother, of which he sees much evidence in Wallace’s work. One story, for instance, he casually diagnoses as “a meditation on his difficult relationship with his mother. . . . In the story—as, he believed, in his own life—a mother’s intense love for and disappointment in her son is the root of his neurosis.”

Especially in the case of a contemporary author, such observations can be limiting, offering us an interpretation that is easy and preemptive, the paper that covers rock. It’s not that the connections are wrong, necessarily, just that we’re tempted to infer too much from them about what is real and true about the work as a whole—in a veteran’s writing about war, or Scott Turow’s writing about lawyers, or Hemingway’s writing about men who fish.

One of Wallace’s peers, William Vollmann, has said, “Of all the arts, although photography presents best, painting and music convey best, and sculpture looms best, I believe that literature articulates best.” Words articulate best perhaps, but central to Wallace’s work is the idea that they can also totally fail and even obfuscate. The epigraph to Max’s book is from “Good Old Neon”: “What goes on inside is just too fast and huge and all interconnected for words to do more than barely sketch the outlines of at most one tiny little part of it at any given instant.” The one-to-one connections Max makes throughout Every Love Story seem to stand against what Wallace identified as the central struggle of writing: He wanted his work to deal with what it was to be, in his words, “a fucking human being,” not what it was like to be David Foster Wallace.

But Max manages to pull off something that reminds us that words can do those other things too: They can present, and loom, and convey. In the hands of a lesser biographer, the anguishing episodes of depression and self-doubt would have seemed like a dreary accumulation of weights bound to tip the scale, but Max presents them as a series of triumphs. Where the side-by-side rendering of personal and artistic struggles missteps when tidy lines are drawn, it succeeds in conveying the artist’s real sense of internal and intellectual warfare, its casualties and its fragile victories, and, most hauntingly, its endlessness. One comes to believe in the possibility of a different ending: Nothing is inevitable.

As Every Love Story draws to an end, Max’s narrative shifts gears into a high-speed reckoning of the final months of Wallace’s life, presenting us with an artist who in many ways had found peace even as the cumulative turmoil had already had its effect. It is what Max conveys here that seems truest of all: Wallace is with us and, in the course of a paragraph, he is gone. This is how many of us might remember it. Everything adds up to this, but Max admirably smudges the formula: Of course it does not.