James Carman, Managing Editor: I’ve always had a yen for historical fiction. I’m an admirer of British novelist Barry Unsworth, for instance, who’s set several brilliant novels—Pascali’s Island, The Rage of the Vulture—around the crumbling Ottoman Empire. And I just finished David Mitchell’s latest, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. I found the early parts of it— an amazingly evocative portrait of the odd Dutch trading post Dejima in late-18th-century Nagasaki—much more compelling than the latter sections; for me, the tale lost some momentum once the action moved from the walled-off island to mainland Japan, but Mitchell’s wonderful writing more than lived up to its reputation, and left me curious to try his more experimental fiction, such as Cloud Atlas.

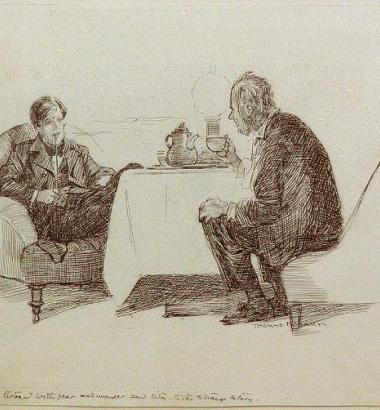

I’m not sure I could say what made me launch into Great Expectations. I know the story well enough from various film adaptations, but I just never got around to reading it. I’m glad I did. I’d forgotten how funny Dickens can be, and how delightfully he names his characters. A moniker such as “Uncle Pumblechook” can only belong to one of literature’s truly pompous fools, whose constant quizzing of the protagonist Pip is deliciously dismissed after the youngster’s first visit to the mysterious Miss Havisham: “The mere sight of the torment, with [Pumblechook’s] fishy eyes and mouth open, his sandy hair inquisitively on end, and his waistcoat heaving with windy arithmetic, made me vicious in my reticence.” Great stuff indeed.

Rebecca Rosen, Associate Editor: I'm also reading a David Mitchell novel—

Cloud Atlas—and loving it. The characters are delightful, and slowly unraveling the ways in which they connect to one another is a great pleasure. Like Jim, I'm hoping to read Mitchell's other novels soon. Apparently, characters from one Mitchell novel can make a cameo appearance in another, a neat trick that draws the reader not just into the private world of a novel, but

an entire "fictional universe."

Steven Lagerfeld, Editor: I treat books a lot like I do web sites: I skim and browse a great deal (a habit fed by the

WQ’s steady flow of review copies) but settle in with only a few. It was only because of

Martin Walker’s review in the WQ that I learned of Simon Winder’s funny, idiosyncratic

Germania: In Wayward Pursuit of the Germans and their History in time to take it along on a plane ride to that strange country, and I’m lucky I did. Winder is an Englishman who early on developed an odd fascination with things German, and he wanders happily from the present down alleyways into history, often jumping off from one of the obscure German locales he favors. It’s illuminating to learn, for example, not merely that before its formal unification in 1871, Germany was a patchwork of states, but that the states ranged from familiar giants such as Prussia (not the military powerhouse it was cracked up to be, in Winder’s view) to “the laughable territory of Anhalt-Zerbst, a place so small it could hardly breathe.” That background is one reason why Germany today is so surprisingly uncentralized. Winder occasionally verges on the pedantic (how could a book on the Germans not?), but he gives a better feel for the country than any academic tract possibly could.

Although I’m no longer a regular reader of fiction, I make it a point to dip in from time to time, and Chang-rae Lee’s A Gesture Life is one of those novels that make me feel I don’t do that often enough. Writing in the first person in prose that evokes the emotional stillness desperately maintained by his central character, an elderly Japanese man who has made his life in America, Lee gradually reveals the wounds of the past that created that stillness and the trials of the present that test it. The writing schools turn out plenty of novelists with impressive technical skills, but Lee has something to show us—about immigrant experience and more—that elevates this book high above the crowd.

Photo credit: "So Pip told him about his legacy and what it had done for him" from Thomas Fogarty's illustration of Great Expectations; Library of Congress