Prickly German Privacy

Germans know how to enjoy themselves during the holidays, but don’t invade their Internet privacy.

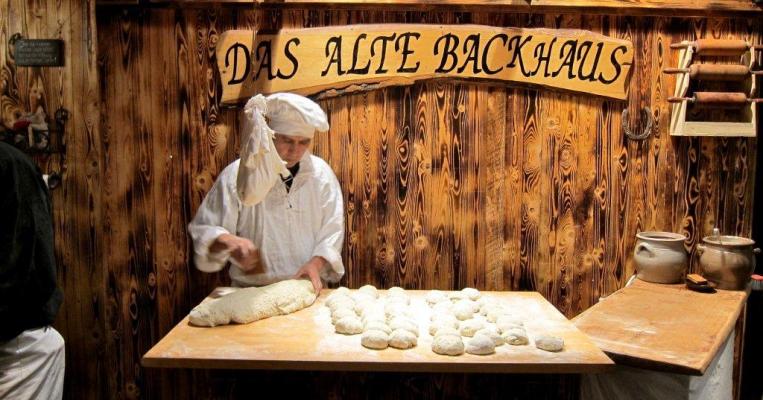

Germans would seem to have modern living down pat. On my wintry weeklong stay there last month, Berlin hummed with activity. People thronged 60-odd Christmas markets, drinking mulled wine and buying up ornaments and trinkets. Cranes loomed over new buildings in what was East Berlin, the dreary capital of communist East Germany. German beer lived up to its billing. There was hardly a whiff of worry in the air.

I was in the country with 14 young American journalists as part of the Berlin Capital Program, a short fellowship paid for by the German Fulbright Commission. Despite the festive atmosphere, I discovered that the Germans do few things better than worry. Parliamentarians, journalists, editors, and academics we met repeated a long list of fears: Greek debt, nuclear power, right-wing nationalists, global warming, the failure of immigrant integration, enduring disparities between former East and West Germany, anti-Semitism, being late to appointments. You can count on Germans to touch every base.

The passion behind one German concern took me by surprise: data protection. Like many Europeans, Germans jealously guard their privacy. They shudder at the thought of government bodies or corporations storing their personal information, perhaps in part because the Nazis and, later, the East German secret police did this with deadly consequences. Companies in Germany cannot keep any personal information on file without specific permission from individuals. The Federal Data Protection Law (or Bundesdatenschutzgesetz to loquacious German-speakers), first passed in West Germany in 1976 and amended several times since, provides the legal basis for privacy protection. It is more stringent than any American equivalents. The law mandates the appointment of privacy protection watchdogs, known as data protection commissioners, in Germany’s 16 states and at the federal level.

The commissioners don’t shy away from a fight. Google ran afoul of them—and similar authorities across Europe and North America—when, between 2007 and 2010, it collected unencrypted data from private wireless networks during street-by-street photographic surveys for its Street View feature within Google Maps. Google claimed it was all an accident, which did little to placate outraged Germans. Prosecutors in Hamburg, where we took a day trip to visit the offices of Der Spiegel magazine, eventually dropped a criminal case against Google. In 2011, a state supreme court in Berlin ruled that, so long as people’s faces and license plates are blurred, Google’s Street View pictures—“accidental” wireless data sniffing notwithstanding—are legal. But the technology giant was sufficiently chastened that it voluntarily halted any expansion of its Street View picture archive in Germany. If Germans dislike the idea of their faceless figures, businesses, or residential facades appearing in Internet photos, they can opt to be blurred out entirely. As of April 2011, nearly 250,000 Germans had gone to the trouble to do so, airbrushing themselves out of Street View existence.

Nor has Facebook been spared. In August, Johannes Caspar, the Hamburg state data protection commissioner who led the charge against Google, cried foul over Facebook’s facial recognition technology, which scans faces in uploaded pictures and suggests friends to tag. Threatened with fines and bad PR, Facebook capitulated the next month and promised to turn the feature off in Europe. Then, just a few days ago, the data commissioner for the northern state of Schleswig-Holstein demanded that Facebook allow users to create accounts with pseudonyms rather than their real names. “It is unacceptable that a U.S. portal like Facebook violates German data protection law unopposed and with no prospect of an end,” Thilo Weichert said in a strongly worded press release. “The aim of the orders of [the state data commission] is to finally bring about a legal clarification of who is responsible for Facebook and to what this company is bound to.”

German law, evidently.

All the handwringing doesn’t keep Germans off the Web. Most of the young people I met had Facebook accounts. What distinguished them from many Americans was their awareness of the Internet’s intrusiveness. If Germany is a bit uptight about protecting privacy, then the United States may be altogether too lax. We could use a little more of their vigilance, not to mention their way with bratwurst and Christmas markets.

Photos: Hamburg Christmas market