Slideshow: Feeding the Future

A writing professor brings her camera to the Salatin family’s famous farm.

Nestled in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, the Salatin family’s Polyface Farm encompasses 550 acres of woodland and pasture. A working farm, it has also become a mecca for the local foods movement. (All photos © Erica Bleeg.)

By Erica Bleeg

Walking through cow pastures and hog paddocks is part of my research. I teach two university courses on writing about food, and have a keen interest in where it’s sourced. Spring is the time to see a farm’s operations in full swing, so I recently headed over to Polyface, a Swoope, Va. farm that thrives without using chemical fertilizers, herbicides, hormones, or antibiotics.

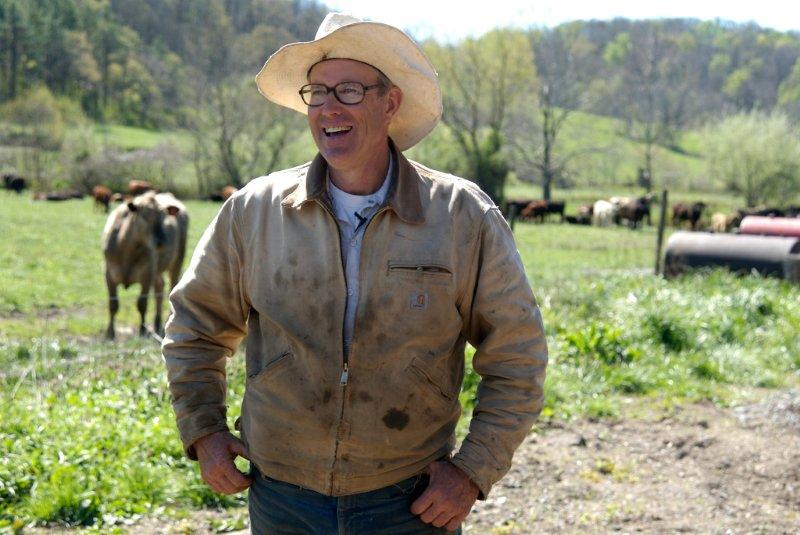

Once known predominantly among readers of the trade journal Stockman Grass Farmer, Polyface’s owner, Joel Salatin, has gained a broader audience through trumpeting his humane and ecologically sound approach to agriculture. The 55-year-old Salatin has also made a mission of cultivating new farmers. For every farmer under 35, there are six over 65, and the USDA predicts that within the next 20 years a quarter of all farmers will retire. “There’s a brain-drain of knowledge about agriculture,” said Salatin.

Beginning wasn’t easy for Salatin. After a stint as a newspaper reporter, he returned to the family farm in 1982. “It was nip and tuck,” he remembered. “We lived on $300 a month.” Now Polyface brings in about eight summer interns in their teens and twenties to help with the season’s blaze of production, and two full-time apprentices work year-round. Salatin’s son, Daniel, lives on the farm with his wife and three children and manages the operation, often directing Salatin the Elder on chores.

Polyface rents an additional 1,200 acres where younger farmers live and work as independent contractors, borrowing equipment and raising livestock that feed Polyface’s business. “They can begin with zero capital,” said Salatin. Two such contractors have since successfully launched their own businesses. “In the end,” said Salatin, “This germinates new young farmers.”

Joel Salatin encourages visiting college students to smell the mix of manure and wood chips lifted from a hog paddock. The hogs aerate it while rooting with their snouts, transforming what could be toxic waste into rich, nearly odorless fertilizer.

Just two to three months old, pigs huddle together for warmth on a brisk April morning. At nine months and weighing about 300 pounds, they’ll be “ready to go,” says 26-year-old apprentice Noah Beyeler, farm talk for “ready for slaughter.” Polyface sells about 50 percent of all pig shoulders and hams to nearby Chipotle restaurants.

With the aid of a forklift, apprentice manager Eric Barth, 26, moves a 308-pound hog feeder toward the barn paddock. Expensive equipment contributes to steep upfront costs for new farmers. According to a survey conducted by the National Young Farmers’ Coalition, 78 percent of farmers cite lack of capital as the biggest challenge to beginners, followed by access to land and credit.

Eric Barth, Daniel Salatin, and Noah Beyeler select pigs whose post-slaughter weight appears to be less than 100 pounds, typical for barbeque. These would fill orders from the British Embassy in Washington, D.C. and an Arlington, Va. restaurant. Polyface also sells its meat and eggs in an on-site store. Seeing these men capture pigs recalls a Ralph Waldo Emerson observation Michael Pollan cites in The Omnivore’s Dilemma: “You have just dined, and however scrupulously the slaughterhouse is concealed in the graceful distance of miles, there is complicity.”

Homemade pens keep broiler chickens on grass and safe from predators. The broilers go out on pasture at three weeks of age; they’ll grow for about five more weeks before reaching processing weight. Here Daniel Salatin refills their water supply. In the last three weeks of life the broilers grow over an ounce a day, he says, and “if any stress—like not enough water or feed—interrupts that growth process, you can’t get that back.”

Barred Plymouth Rock hens roam the pasture that cattle grazed only the day before. The hens follow the cattle, picking protein-rich grubs from cow patties, aerating the soil as they peck, and fertilizing it with their own nitrogen-dense droppings. In the backdrop is one of Joel Salatin’s inventions, the portable eggmobile where hens lay eggs in interior cubbyholes.

Unlike cattle finished on manure-laden feedlots, and fed a potentially poisonous mix of corn and antibiotics, the cattle at Polyface feed on grass, their natural diet.

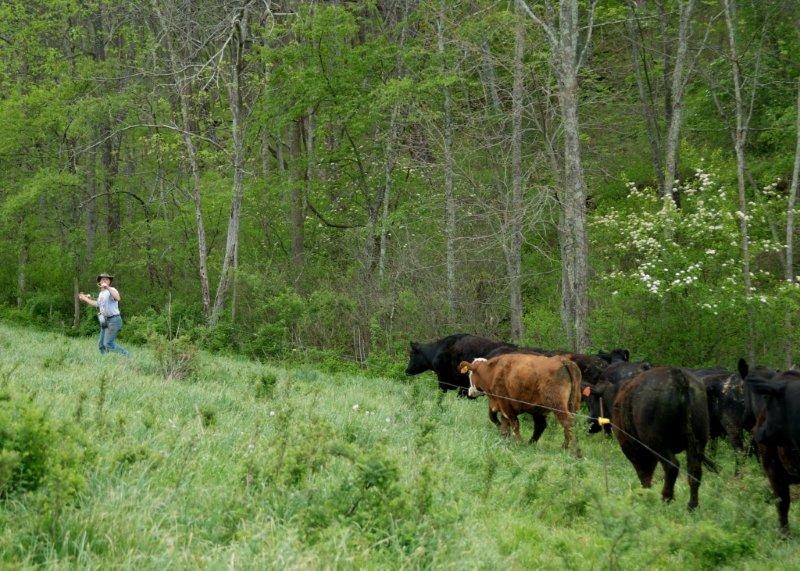

“What you never, ever want to do is violate the law of the second bite,” Joel Salatin once advised Michael Pollan. A single bite at the top of the grass is optimal for stimulating regrowth. To prevent overgrazing, the cattle at Polyface are moved almost daily to fresh pasture, a process that takes Daniel less than five minutes.

Daniel points to two cattle bringing up the back: “See how the mother cow walks a little and then she’ll stop, waiting for her calf to catch up?”

Of continuing the work of his father’s business, “I’ve never thought of doing anything different,” Daniel says. The chore he most enjoyed as a child was herding cattle. Here, his two sons lend a hand.

Joel Salatin, a Christian, considers his work “a ministry in every sense of the word, except we’re for profit. We are in the healing business: healing the land, healing the food, healing the culture. Ultimately, if our work is not healing, it’s not worth doing.”