Practice Isn’t Everything

The “magic number of greatness” debunked.

The “magic number of greatness” debunked.

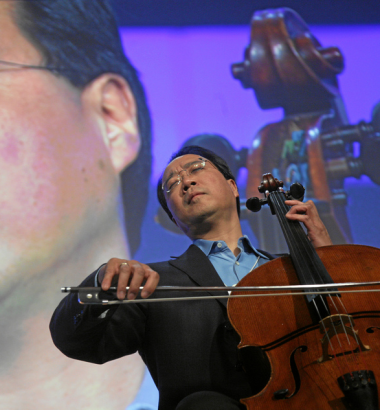

Want to give master cellist Yo-Yo Ma a run for his money? Practice the cello for 10,000 hours.

Such is the straightforward but grueling path to becoming an expert performer, according to a landmark 1993 study by Swedish psychologist K. Anders Ericsson and two colleagues, Ralf Krampe and Clemens Tesch-Romer. They found that the best violinists and pianists at a German music academy had tallied an average of more than 10,000 hours of practice before they turned 20. Lesser players weren’t as dedicated. Practice time, not innate talent, sets extraordinary performers apart, Ericsson and company concluded.

The world seized on the study as evidence that expert achievement is open to all: Work hard enough on the piano, and you’ll have a shot at Carnegie Hall. Superstar writer Malcolm Gladwell gushed in his bestseller Outliers (2008) that “ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness.” He claimed that the formula helped explain the success of people as diverse in their talents as the Beatles and Bill Gates.

Critics have lambasted the theory. What about the hard-working strivers who fall short, and the prodigiously talented people who practice less but shine anyway? Now the doubters have data to back them up.

Michigan State University psychology professor David Z. Hambrick and five other psychologists sifted through data from 14 studies of performers—six of chess players and eight of musicians. Writing in Intelligence, the authors report that a full quarter of the master chess players they examined achieved elite status after only 7,500 hours of practice. And more than 20 percent of the best players made even quicker work of the process, becoming masters in 5,000 hours or fewer. Meanwhile, a sizable contingent of lower-ranked players trudged through more than 10,000 hours in the company of pawns and kings without making the grade. “Some people require much less deliberate practice than other people to reach an elite level of performance in chess,” Hambrick and his colleagues explain. Overall, differences in lifetime practice totals accounted for only 34 percent of the variation between players of different skill levels.

The 10,000-hour theory—a period of time roughly equivalent to 10 years of formal training, according to Ericsson—also fell flat in musical performance. Data published in 1993 by Ericsson and his colleagues actually underscore the point, Hambrick and his coauthors say. While the best pianists at the German music academy had indeed all logged at least 10,000 hours of practice, some practiced as many as 30,000 hours before they attained keyboard perfection.

What explains such disparities? Previous studies have shown that chess players who begin training at a younger age have a leg up on competitors, regardless of practice time. Likewise, many legendary classical composers started writing music at a young age and made their first contributions to the field more quickly than peers who started later. “There may be a critical period for acquiring complex skills just as there may be for acquiring language,” the authors note.

Smarts count, too. Multiple studies have shown that musicians with exceptional working-memory capacities and high IQs outshine their peers. According to a 1992 study, outstanding young chess players also have high IQs.

Grit and passion can still pay off, of course. One chess player in the 2007 study persisted for 26 years before reaching master status, even as another player in the same study became a master in a mere two years.

Hambrick and company don’t mean to crush anyone’s dreams. They want people to be realistic about what’s possible given their talents. Ten thousand hours of toil may not put you on par with the masters. But if people assess their prospects and abilities with open eyes, “they may gravitate toward domains in which they have a realistic chance of becoming an expert.”

THE SOURCE: “Deliberate Practice: Is That All It Takes to Become an Expert?” by David Z. Hambrick, Frederick L. Oswald, Erik M. Altmann, Elizabeth J. Meinz, Fernand Gobet, and Guillermo Campitelli, in Intelligence, May 15, 2013.