I Want a New Drug

American pharmaceutical firms are producing as many breakthrough drugs as ever.

American pharmaceutical firms are producing as many breakthrough drugs as ever.

Grisly stories of flesh-eating bacteria and uncontrollable staph infections have raised the alarming possibility that pharmaceutical scientists are losing the race with disease. It’s true that the number of new drugs approved each year by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration hasn’t changed much since the 1980s. Indeed, there has been a sharp drop in approvals since the mid-1990s. But Michael Lanthier and his colleagues, all of whom hold research or other positions at the FDA, say that all drugs are not created equal. Grouping new drugs by their level of significance reveals a far more encouraging picture.

The researchers divided new drugs—what they call “new molecular entities”—into three categories. The most valued of all were “first-in-class” drugs that have opened “a new pathway for treating a disease.” The antidepressant Prozac and the statin Mevacor (which lowers cholesterol), both approved in 1987, are good examples. Both were breakthrough pharmaceuticals that paved the way for many other new drugs. The second category was “advance-in-class,” which included pharmaceuticals that “potentially offer major advances in treatment” within an existing class of drugs, often targeting serious diseases such as cancer and HIV. “Addition-to-class” was the label applied to a compound that isn’t safer or generally more effective than existing drugs (though some individuals may benefit from its use significantly). For example, beta-blockers, which are used in the treatment of high blood pressure, have been around long enough to spawn many addition-to-class versions.

After winnowing certain drugs (such as those intended only for military use) from the list of those approved between 1987 and 2011, Lanthier and his coauthors came up with a total of 645 new drugs. Thirty-two percent of them were first-in-class drugs, while 22 percent represented significant advances. Forty-six percent were addition-to-class drugs.

Throughout the 25 years covered by the researchers, first-in-class drugs steadily appeared at an average rate of eight per year. Small and large pharmaceutical companies produced the same number of breakthrough drugs, on average, but after 1996 the innovative edge seemed to shift to the smaller firms, which increased their share of all drug approvals from about a third to half.

What about the decline in drug approvals since the mid-1990s? That is largely a mirage produced by a momentary surge in new addition-to-class drugs in 1996 and ’97. Lanthier and his colleagues can’t explain the increase, but they note that it came on the heels of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992, which brought with it a big increase in the number of FDA staff drug reviewers.

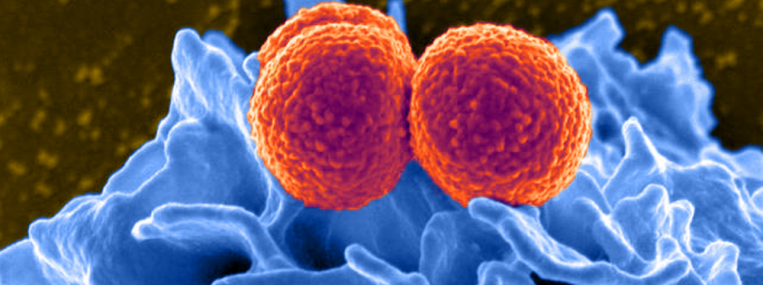

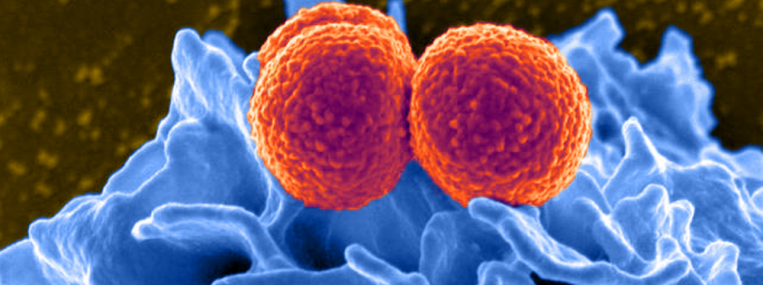

None of this argues for complacency, the authors note. There’s an urgent need for innovative new drugs, especially for the treatment of “antibiotic-resistant infections and rare pediatric disease.” Policymakers have already done much to speed innovation; the focus now is on pouring more money into research and speeding the drug approval process. Such efforts “should have an impact on innovation in drug development during the coming decades.”

THE SOURCE: “An Improved Approach to Measuring Drug Innovation Finds Steady Rates of First-in-Class Pharmaceuticals, 1987–2011” by Michael Lanthier, Kathleen L. Miller, Clark Nardinelli, and Janet Woodcock, in Health Affairs, August 2013.