The Faith of a "None"

Even for nonbelievers, religion has its uses.

Even for nonbelievers, religion has its uses.

Conservative columnist George F. Will is a “none,” and he’s proud of it. That is, he places himself firmly among the 20 percent of Americans who simply respond “none” when polled about their religious affiliation. But there’s at least one thing setting Will apart from many of his unaffiliated peers: He thinks religious institutions “play a crucial role in sustaining our limited government” and that citizens “should be friendly to the cause of American religion, even if they are not believers themselves.”

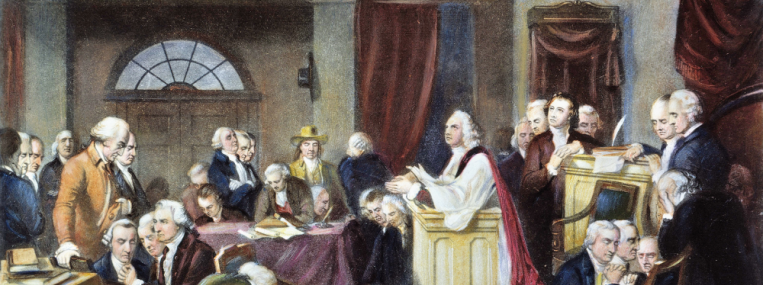

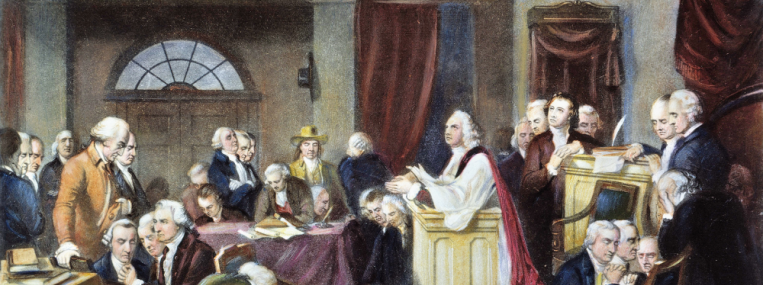

Will is in good company. Many of the Founders could hardly be considered conventionally religious. “George Washington famously would not kneel to pray,” and when his pastor rebuked him, he simply stayed away from church on Communion Sundays. James Madison brushed off the religious impulse altogether, saying that “the mind prefers at once the idea of a self-existing cause to that of an infinite series of cause and effect.” Yet the Founders emphatically backed religion—Washington called it one of the “indispensable supports” of American politics, along with morality. Two days after Thomas Jefferson wrote his famous letter calling for a “wall of separation” between church and state, he attended one of the church services regularly held in the House of Representatives.

The Founders’ attitude reflected the understanding of government articulated in the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, That all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable Rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men.” The purpose of government, in other words, is to “secure” pre-existing rights that all people possess, not to create and dispense them.

But a government that is not in the business of defining the nature of happiness, virtue, or excellence cannot be indifferent to such questions. “Having such opinions is the business of other institutions—private and voluntary ones, especially religious ones, that supply the conditions for liberty,” Will explains. The Founders recognized that “religion plays a large role in nurturing the virtue that republican government presupposes.”

Such ideas, so revolutionary in their time, now sound antique to many. And Will argues that we can thank President Woodrow Wilson for that. “Wilson disparaged the doctrine of natural rights as ‘Fourth of July sentiments.’ He did so because this doctrine limited progressives’ plans to make government more scientific in the service of a politics that was more ambitious.” Casting aside natural rights and the idea of limited government, Will writes, Wilson recast the Constitution as a “living” document so that government could bend it to secure “powers sufficient to whatever projects were required for progress.” Wilson wrote that government should be “an instrumentality for quickening in every suitable way . . . both collective and individual development.” Charismatic leaders in the White House—alien to the Founders’ thinking—would chart the nation’s course.

Of course, Wilson wasn’t solely responsible, Will allows, but his ideas played a large role in creating our “modern, administrative, regulatory state, from the supervision of which no corner of life is immune.”

Modern government tends to crowd out civil society by assuming its functions, and to the extent that it undermines religion, it “threatens society’s vitality, prosperity, and happiness.” Will quotes the neoconservative thinker Irving Kristol: “Nothing is more dehumanizing, more certain to generate a crisis, than to experience one’s life as a meaningless event in a meaningless world.”

People deprived of meaning look for solace in pleasures and distractions and, all too often, Will writes, in new kinds of faith. “The excruciating political paradox of modernity is that secularism advanced in part as moral revulsion against the bloody history of religious strife. But there is no precedent for bloodshed on the scale produced in the 20th century by secular—by political—faiths.”

THE SOURCE: “Religion and the American Republic” by George F. Will, in National Affairs, Summer 2013.