Welcome to the Jumble

What place do neighborhoods have in modern cities?

What place do neighborhoods have in modern cities?

In a San Francisco hotel room not long ago, I absently flipped through one of those forgettable in-room lifestyle magazines aimed at the casual visitor. Set amid ads for marbled steak and glistening sushi, a tourist map occupied the last pages. As do most urban maps, it had segmented the city into its various and iconic neighborhoods—Pacific Heights, the Mission, Haight-Ashbury.

Gazing at this depiction of a city I know only from a smattering of disjointed visits and impressions, I was struck by the regularity in the distribution and size of its neighborhoods. I had the sense that what I was looking at was the expression of some kind of logic—but whether it was the result of government fiat or some curious social alchemy was beyond me. It left me wondering: Is there some human penchant for breaking up space to better fit our cognitive maps?

Neighborhoods often exist as much in the collective imagination as on urban ground, their borders shifting depending on who draws them. Contrast a map of San Francisco neighborhoods produced by the municipal planning department with another effort—this one created by the city’s realtors’ association—and the activity becomes a children’s game of “spot the differences.” The realtors’ map brims with Candlestick Points, Barbary Coasts, and Yerba Buenas; the names sound like the result of fanciful branding exercises rather than designators of actual places to live.

It is frequently, almost reflexively said of Chicago, Saul Bellow’s “somber city” where I was born, that it is “a city of neighborhoods.” Indeed, the city does exude vital local identities within its larger boundaries. But if Google is to be believed, so too is Boston a “city of neighborhoods.” As are Saint Louis, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Not to mention Los Angeles, Miami, and Dallas. Detroit, that city on the brink? Long a city of neighborhoods. With my exercise beginning to turn dully repetitive, I started looking for exceptions. Perhaps Phoenix, with its legendary sprawl? No—there, nestled high in the search results, was the following claim: “Phoenix is a city of neighborhoods, each with a unique personality of its own.”

After plugging in every burg from Tampa to Topeka, I finally hit on a major municipality that did not answer the summons of my keywords: Las Vegas. It may be many things to many people, but apparently Las Vegas is not a city of neighborhoods.

I had come to the realization that “city of neighborhoods” is a virtual tautology, a truism so often repeated that it no longer seems to explain much. Perhaps it was time to go back and unpack the word “neighborhood,” frequently invoked yet seldom analyzed. What is a neighborhood? How do neighborhoods relate to the larger city? How much influence do neighborhoods exert in their residents’ lives? And in an era of global cities and digital communities, do we even need neighborhoods?

In a 2010 article in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Michael E. Smith of Arizona State University wrote that “the spatial division of cities into districts or neighborhoods is one of the few universals of urban life from the earliest cities to the present.” In late medieval Marseille, he noted, quarters—in essence, neighborhoods—were important sites of social identity, oriented largely toward one’s profession; Smith cited research that found that “close to 70 percent of all craftsmen whose residences are known lived in the quarter associated with their craft.” In Aztec cities in Mexico, he pointed to clusters of houses that could be “confidently identified as neighborhoods” that were organized around a calpolli, a social unit composed of many often-related groups. Archaeologists are now even suggesting that Mayan settlements—which, Smith observed,were once not even deemed “real” cities—had neighborhoods.

Our view about how ancient people lived is partially viewed through the lens of mid-20th-century academic sociology—from which Smith’s own definition of neighborhood (“a distinct territorial group, distinct by virtue of the specific physical characteristics of the area and the specific social characteristics of the inhabitants”) was drawn. Indeed, much of our thinking about neighborhoods dates to the 1900s.

While the word “neighborhood” first appeared in written English in the 15th century, the current usage did not emerge until much later. The historian Carl Abbot, for instance, argues that in late-18th-century New York City—contrary to notions that citizens lived largely in a socioeconomic mishmash—“residential neighborhoods were in fact differentiated according to wealth and occupational status.” He calls them (with hindsight) neighborhoods, but, curiously, the word itself does not begin to appear in The New York Times until the late 19th century. In 1894, in one of its earliest uses, the Times declared, “Nobody can fail to sympathize with the efforts of the worthy people who are trying to purge certain neighborhoods in the city that have become disreputable.”

The neighborhood began to acquire new conceptual currency around that time—as the prominent urbanist and New Yorker architecture critic Lewis Mumford suggested in a 1954 article in Town Planning Review—precisely because it was under threat. The “spontaneous neighborhood grouping” was falling victim to industrial capitalism’s rapidly intensifying income and place segmentation, Mumford argued, while the advent of wheeled transport changed planners’ emphasis from “facilities for settlement to facilities for movement,” destroying neighborhood texture even as it brought different parts of town closer together (and created new, suburban neighborhoods). Planners wondered how to find the means, in the ever-growing metropolitan regions, to make life feel more local. In a 1929 monograph, the planner Clarence Perry coined a term for the concept used in planning communities such as Sunnyside, Queens, and Radburn, New Jersey: “the neighborhood unit.”

“What Perry did was to take the fact of the neighborhood and show how, through deliberate design, it could be transformed into . . . the modern equivalent of the medieval quarter or parish,” Mumford wrote. What no longer existed organically—the sense of community gained by people living and working in proximity to each other, their movements restrained by how far they could walk or what they did for a living—could be reverse engineered. Perry envisioned his neighborhood unit as encompassing 160 acres (with a housing density of 10 units per acre) and having about 7,000 residents. It would be laid out around a school positioned “so that a child’s walk to school [would be] only about one-quarter of a mile and no more than one half mile and could be achieved without crossing a major arterial street.” (Perry would not live to see the time when most American children would stop walking to school.) Arterial roads and shopping complexes would be pushed to the edges, with local streets designed to discourage cut-through traffic.

Perry’s monograph became a virtual bible for planners and developers for decades to come. As the American Society of Planning Officials noted in 1960, Perry’s neighborhood unit was more or less replicated from coast to coast: “Thus one might feel just as at home, or just as lost, on the curvilinear streets of a ‘desert mesa’ in Arizona, at the neighborhood super-shop in ‘Prairie Estate’ in Illinois, or in the centrally located elementary school in a ‘Rolling Meadows’ in Pennsylvania.”

Perry’s scheme was not without its critics. The Harvard planning professor Reginald Isaacs argued that its form and execution promoted segregation and exclusion, and that its focus on schools neglected the needs of other residents. Jane Jacobs, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), charged that “as a sentimental concept, ‘neighborhood’ is harmful to city planning,” leading to “attempts at warping city life into imitations of town or suburban life.” While no one might appear more neighborhood-centric than Jacobs, the champion of Greenwich Village, she noted a “seeming paradox” of modern urban life—that to keep people attached to a neighborhood, cities needed “fluidity and mobility.” For the street-level neighborhood to survive, it had to mesh with the texture of the city. She saw a confining sterility in Perry’s units, and lauded Isaacs and others who had “daringly begun to question whether the conception of neighborhood in big cities has any meaning at all.” What she was really after was not, as she put it, a self-contained “artificial town” or pure simulacrum of “village life” in the metropolis, nor a meaningless planning unit without some “means for civilized self-government.” Her ideal existed somewhere in between.

As elusive as that Goldilocks medium was, in the 1960s the idea of the urban neighborhood was on the ascent again as an organizing principle and way of life; the reason, as half a century earlier, was that it was under threat. In a context of urban renewal, the revolt against new freeways, and changing demographic profiles, neighborhoods became the locus of social cohesion, whether underpinned by an impulse toward social inclusion or exclusion. It was during this period, for example, that the phrase “There goes the neighborhood,” with its echoes of “white flight,” began to enter the lexicon.

The Brooklyn neighborhood next to mine was formed by just such a midcentury crisis. Cobble Hill, a landmarked, tony district of elegant townhouses peopled by bankers, “bobos” (bourgeois bohemians), and cultural mandarins such as the novelist Martin Amis, seems an eminently historic district. But as The New York Times noted in 1960, “It is not a well-known area—it had no name until two years ago.” The event that precipitated the emergence of a recognized neighborhood was the announcement of plans to construct a supermarket. Around the same time, efforts at “slum clearance” began. Residents, many of them newly drawn to the area and looking for more affordable alternatives to affluent Brooklyn Heights, formed a homeowners’ association. They named the newly conceived neighborhood after a fort that had stood in the area during the Revolutionary War (“Cobble Hill” sounded better than the name early Dutch settlers had come up with—“Punkiesburg”), and out of the cartographic muddle of South Brooklyn was born a “new” neighborhood, one that eventually shook off vaguely threatening economic torpor and became the place it is today, replete with single-origin coffee and well-regarded public schools.

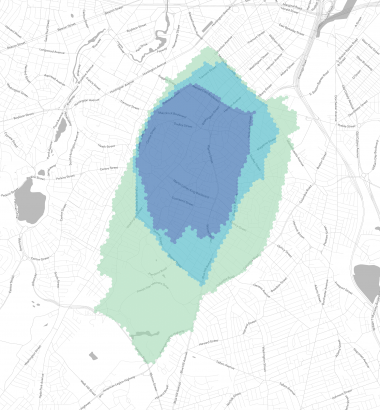

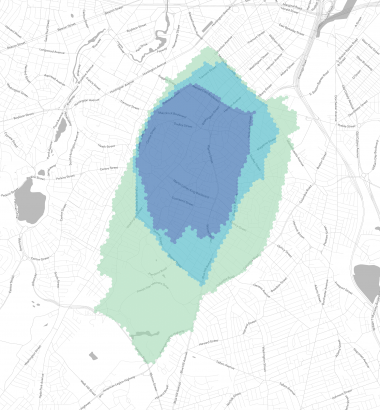

Everyone has heard the complaint about a neighborhood being “invented” by realtors hoping to stake out new price points or protect old ones, but every neighborhood requires some initial fusion of cartography and mythology to spring into being, and imposed or artificial boundaries do appear to shape community life. A project in Boston shows how people’s conceptions of neighborhood boundaries often relate to—and differ from—more formalized strictures, in this case, the all-important municipal parking permit zones.

Another project, Livehoods, developedby Justin Cranshaw and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Computer Science, uses social media data (tweets and Foursquare “check ins”) that reveal where people actually spend their time in a city. Often, the patterns of activity and neighborhood boundaries match up—particularly when a neighborhood is bounded by strong geographic features. In many cases, however, neighborhoods may be split into different groups of users; or, particularly in neighborhoods in flux, people’s movements may spill across the edges of various neighborhoods, forming new social territories. As Cranshaw told me, in cities such as Tampa, city planners are using Livehood techniques to help optimize the allocation of services to new developments, and to envision how those developments connect to established neighborhoods.

It has become a bit of an urban sport to create (and then joke about) increasingly baroque neighborhood names—the SoPaNoMaHos—but research suggests that local awareness of neighborhood names and map boundaries is connected to various indices of social capital. One study found, for example, that “groups with more shared local ties are more able to supply a neighborhood name.” Other studies have found positive correlations between neighborhood naming and relatively high homeownership levels, residential stability, and fewer police calls.

A 1984 study of neighborhood affinity in Baltimore published in Population and Environment found that the “race variable” had the “strongest direct effect” on neighborhood identification. The researchers surmised that the city’s African-American residents, often living in perceived “high-threat” areas, “collapsed” the sense of their neighborhoods into their own blocks, thereby trimming a dangerous world to a manageable size. Surely this happens on many levels: In my own neighborhood, there are summer “block parties,” not “neighborhood parties,” as if to reinforce the idea of the city block setting the outer limit to some kind of social cohesion.

Is there an ideal neighborhood size? In 1981, the noted urban planning professor Kevin Lynch championed the “very local unit,” containing anywhere from 100 households to as few as 30 or 15. The spirit of Lynch’s idea exists today in architect Ross Chapin’s concept of “pocket neighborhoods,” groups of houses clustered around a courtyard or shared open space, built, as Chapin has said, “around the fact that our human nature is social.” Curiously, the physicist and networks expert Albert-László Barabásiand colleagues, looking at mobile phone activity, found that human “spatial clustering” (the geographic proximity of members in a community) begins to expand greatly once community size reaches 30. As the community grows, its geographic span grows—but at a much greater rate. “This suggests that the tendency of human groups to remain geographically cohesive gradually gives in as the group size exceeds 30.” The number 30, Barabási and colleagues add, also seems to be the optimal number for achieving cooperation in laboratory experiments on group behavior.

Whatever size neighborhood we live in, we are likely to further rearrange it in our own conception. The writer Jonathan Raban, reflecting a few decades after the publication of his influential 1974 book Soft City, which proposed the idea of the “city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare,” talked about the liberating quality of the metropolis, where you were not “stuck” with your neighbors, as in suburbia, but could construct your own personal city. He wondered, as critics such as Mumford had done before, whether gentrification and increasing class segmentation were destroying that sense of possibility. Perhaps the Internet, where his daughter dwelt in an “elective community of exactly the kind I once sought in the big city,” was where the soft city now resided. Perhaps social networks and the like were the new neighborhoods, not of proximity, but interest.

But Raban’s whole supposition, of the freedom, essentially from one’s context, that could be found in the city, ignores one thing: For many urban residents, neighborhoods are more than fictive constructs. They are real, and they are the very stuff of life and death.

In the city of Chicago, where you reside has an enormous impact on your destiny. In large swaths of the city, there is nothing “soft” about it; the fact of one’s geography is as hard as one’s life. Low birth weights and high homicide rates cluster in geographic hot spots, Harvard’s Robert J. Sampson writes in his ambitious study Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect (2012). That should come as no surprise—the surprise, Sampson learned, was that those troubles cannot be explained by poverty alone. After adjusting for income, he found that some neighborhoods in his study were still healthier and safer than others.

Sampson recreated a classic “pro-social behavior” experiment in Chicago, dropping stamped, addressed envelopes across the city. Would where the letter was dropped affect how often it was returned? In theory, it should not: There are no income or institutional barriers to picking up a letter. But Sampson found clear neighborhood-level differences in letter-return rates; moreover, he found that those areas with the highest rates—where people were in essence more “neighborly”—tended to be the ones with the lowest rates of violent crime.

Neighborhoods, Sampson found, can become something more than the sum of their parts. He argues that social ties need be neither deep nor extensive to make healthy neighborhoods; indeed, he suggests, many people would rather not have their friends as neighbors. They just want people they can trust to help look after the common good. “When ties are ‘thick,’ it may even be that outcomes are worse rather than better,” he notes. For me, that rings true: In my many years in Brooklyn, while I have been friendly with neighbors I know, and some of my closest friends have become my neighbors, I have not become good friends with anyone simply because that person was my neighbor.

Despite the ideas, promulgated by the digital age and the “flatness” of globalization, that “the city is more or less a random swirl” and that “anyone (or anything) could be here just as easily as there,” Sampson’s work reminds us that place is more important than ever.Though their obsolescence has been prophesied at various points, neighborhoods remain a vital—perhaps the most vital—way of thinking about the modern city.

In the digital age, it sometimes seems as if we merely inhabit the far-flung contours of our various social networks. But this leaves a hole in the center, one that, curiously, an online startup called Nextdoor is trying to fill. Noting that only about two percent of one’s Facebook “friends” are actual neighbors, Nextdoor hosts private social networks for neighborhoods. Its avowed mission: “To bring back a sense of community to the neighborhood, one of the most important communities in each of our lives.” It has been said of the limits of placeless digital globalization, that you can’t hammer a nail over the Internet—but maybe you can borrow a cup of sugar.