Africa's Long Spring

In a process almost unnoticed by the rest of the world, Africa has become significantly more democratic since the early 1990s. Its transition toward political freedom offers both inspiration and cautionary lessons.

In a process almost unnoticed by the rest of the world, Africa has become significantly more democratic since the early 1990s. Its transition toward political freedom offers both inspiration and cautionary lessons.

Long before it came to the Arab world, spring swept through sub-Saharan Africa. In 1990, Mozambique drafted its first multiparty, democratic constitution. The next year saw multiparty elections in what had been one-party states in Benin, Gabon, and Zambia, as well as the overthrow of Mali’s dictator and, subsequently, the election of new leaders. Every succeeding year brought new steps forward for democracy—in Ghana, Kenya, and the Republic of the Congo in 1992, and elsewhere on the continent in subsequent years. The world only paid attention when South Africa joined the ranks of democratic nations in 1994.

Many of the states making the transition to democracy have since suffered setbacks, but just as many have weathered the storm and function today as multiparty democracies. Certainly the transition cannot be called complete, but it has gone much further than many recognize. The Africa I first came to know as a young Foreign Service officer in 1970 no longer exists. It was a continent still in the throes of colonialism in some areas, with wars of liberation being fought in the Portuguese territories of Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe. Apartheid still reigned in South Africa, victimizing a vast black majority of perhaps 24 million. Colonial rule was in its final years in Rhodesia and Southwest Africa, but white minorities still clung tenaciously to power. The Comoros, Seychelles, Djibouti, and Western Sahara had yet to gain their independence from their colonial masters. In many other African nations, the exhilarating winds of change that had swept through the continent as they shook off their colonial yokes after World War II had been stilled, as a myriad of “big men” took power in country after country, either through arrangements with departing colonial rulers or in coups d’état.

Some of the new leaders were popular, usually because they had led the fight against a colonial power and now claimed the mantle of liberation leader. But even those who did not rule through violence and intimidation showed little interest in pursuing political freedom for their people. Caught up in corruption, they moved to close whatever democratic political space remained in their countries as their objectives increasingly narrowed to one: keeping themselves in power. Brutality was the rule, and many an African big man built his authority on the foundation of a ruthlessly efficient secret police, notably Jean-Bédel Bokassa in the Central African Republic and Milton Obote, and later Idi Amin, in Uganda. During his reign in Uganda between 1971 and ’79, for example, Amin killed hundreds of thousands of political and ethnic “enemies.” Often the former colonial powers averted their eyes from the horror in order to preserve their commercial interests, as France did in the Central African Republic, where it tolerated Bokassa, and Gabon, where it underwrote the election fraud of President Omar Bongo.

For the superpowers, Africa in the 1970s was little more than a pawn in the Cold War. The United States and Soviet Union vied for the loyalty of African states by providing aid and other support, and often used their power to manipulate local politics. The United States supported governments it thought would resist Soviet pressure to move into the “red” column. The Soviets courted leftist governments. Both demanded their clients’ support for their pitched battles in the UN General Assembly. In return, the superpowers agreed to turn a blind eye to their clients’ brutal and corrupt governance.

The United States, for example, did not care that Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) relentlessly oppressed his people during his long reign (1965–97) and siphoned off massive amounts of foreign aid and mineral revenues for himself and his supporters. He could be counted on as an ally against the Soviets and Chinese. At one point, it was rumored in the diplomatic community that Zaire consumed more French champagne than France itself. Mobutu, who owned at least two chateaus in Europe, was known to charter the supersonic Concorde for shopping trips abroad. China played a similar game, supporting clients in exchange for recognition and support for their aspiration to displace Taiwan as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Some big men—such as Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia, and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania—were not as brutal as many others, but they played the Cold War game along with the rest and ran centrally controlled economies of “African socialism” that left their people impoverished.

If there was a pretense of democracy during the first few decades of independence—roughly from 1958 to 1990—it was “dominant-party democracy,” but that was only a euphemism for autocracy. Both the international community and Africans voiced support for democracy promotion, but most viewed this exercise as a charade. The Organization of African Unity (OAU), founded in 1963, carried in its charter a sacrosanct codicil that no African state could violate the sovereignty of another for any reason, including oppression or even the massacre of its citizens. The continent’s leaders remained not only inert but silent in the face of even the most horrifying violations. Rarely was an African big man criticized or challenged. The only breach of this principle that I know of came in 1972 when Tanzania aided Milton Obote in trying to recapture Uganda from the man who had deposed him, Idi Amin. That effort failed, but it nevertheless caused great discomfort at the OAU’s 10th-anniversary summit the next year in Addis Ababa, when both leaders attempted to be recognized and seated as the legitimate head of state of Uganda. Two years later, Amin was named the OAU’s chairman.

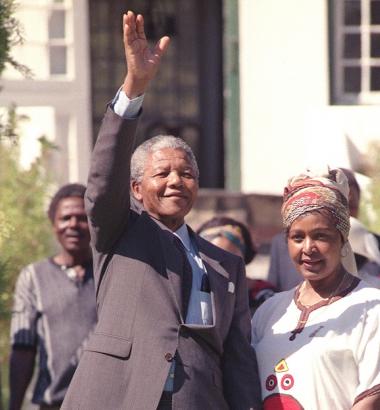

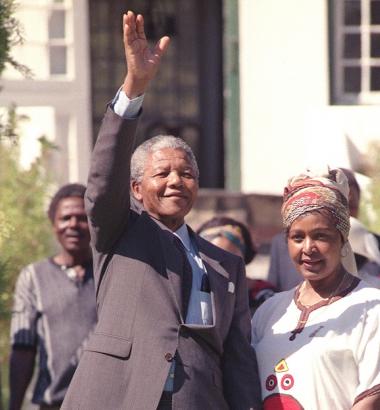

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the Cold War logic that virtually guaranteed a foreign patron to any leader willing to sell his UN vote crumbled with it. Changes were already afoot in white-ruled South Africa, a development almost unthinkable to most observers, who saw the country headed only for chaos and probably a race war of apocalyptic proportions. In fact, there had been a few hopeful signs. South Africa had helped broker the deal that ended white minority rule in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1978, and it had gradually loosened its hold on Southwest Africa, which became independent Namibia in 1990. That same year, F.W. de Klerk’s Afrikaner government lifted the ban on pro-liberation political parties in South Africa and began releasing hundreds of political prisoners, including Nelson Mandela. The next year, it inaugurated negotiations among virtually all parties in the country that ultimately led to an overhaul of the constitution and, in 1994, the first-ever all-inclusive elections. By then, the Soviet Union had gone to its grave. De Klerk and Mikhail Gorbachev were to be forever enshrined in history as the leaders who gave in to the masses, who saw the writing on the wall and chose self-preservation over trying to maintain unfettered power.

Africa’s frustrated masses were inspired by the demise of the Soviet Union and the rebirth of South Africa, and calls for change began to reverberate more loudly through the continent. The big men, facing a new reluctance among international donors to underwrite their autocratic regimes and the unprecedented growth of civil society organizations, began to respond. They scheduled elections and began at least to show the institutional face of democracy by writing constitutions, setting up supposedly independent judiciaries, and allowing multiparty elections. Yet the big men were not ready to give up easily, and they manipulated elections, put off constitutional conventions, bought off or intimidated the opposition, and sometimes just ignored the verdicts of the voters, hoping the West would be more interested in stability than in true democracy.

From abroad, the old rulers faced a new kind of pressure: Aid was increasingly tied to meeting certain standards. The term used by the U.S. government was “conditionality,” which meant that the extension of aid was dependent on a country’s progress toward such goals as raising living standards, holding free and fair elections, and opening up opportunities in education, employment, and development. This approach first appeared during the economic crises of the 1980s with the structural adjustment programs of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, policies that caused near rebellion among recipient countries as they were asked to implement austerity programs rivaling those that, more recently, have been imposed on Greece, Spain, and Italy by the European Union.

Nowadays, the principle of conditionality is well established among aid donors. The U.S. government’s Millennium Challenge Corporation, established in 2004, gives billions of dollars in aid, but only to countries that commit to “good policies,” which the corporation defines as “ruling justly, encouraging economic freedom, and investing in people.” That means enacting market-oriented policies designed to open economies to competition, fight corruption, and encourage transparent business dealings. In addition, governments must invest in their citizens’ health care and education.

With all the pressure for the establishment of democracy in Africa, is it really happening? Multiparty elections have become commonplace, with sitting presidents sometimes losing and stepping down peacefully. In some cases, ruling political parties, which often hold sway through a succession of presidents, have accepted the verdict of the voters. This has happened in Mauritius, Ghana, Somaliland, Zambia, Cape Verde, Benin, São Tomé and Príncipe, Botswana, Senegal, Namibia, and elsewhere. The record has not been as inspiring in countries such as Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Ivory Coast, and Ethiopia. In these countries, ruling parties and presidents still manipulate the political process. Kenya’s Daniel arap Moi, for example, called for multiparty elections in 1992, and every election since has been contested. But violence, intimidation, and a victory by Moi’s Kenya African National Union party were the predictable result every time, until 2002, when it lost. Because of Kenya’s strategic and economic importance and its overall stability, the international community always found a way to accept the results. Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country, endowed with enormous oil wealth, also gets a free pass. Most foreigners are eager to get on with business.

But electoral chicanery rarely happens anymore without challenges from the people and the international community. Coups, which occurred at the rate of about 20 a decade through the 1990s, are now much less common. There have been only six since 2000, and one of those, in Guinea-Bissau, resulted in the coup makers holding democratic elections. And while political violence occurs frequently—notably in Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan, Mali, and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo—the era of constant coups d’état is over. Strikingly, the African Union, the organization that replaced the OAU in 2002, has changed the old organization’s non-interference codicil and created a “peer review” mechanism to monitor democratic progress. It does not recognize governments that come to power through a coup.

Freedom House,an American organization that monitors political freedom around the world, lists 30 of 49 sub-Saharan African countries as “free” or “partly free.” In its “Democracy Index 2011,” the Economist Intelligence Unit, which uses a different set of criteria, counts 21 African countries as “full” or “flawed” democracies or hybrid regimes, and 23 as autocratic.In an earlier report, it said that “the number of elections held annually in recent years has increased; since 2000 between 15 and 20 elections have been held each year. African democracy appears to have flourished and the holding of elections has become commonplace, but not all ballots pass the test of being ‘free and fair’ and many have been charades held by regimes clinging on to power. Similarly, coups d’état have become more infrequent, although conflict, failed governments, and human rights abuses remain widespread. For every two steps forward over the past 20 years there has been at least one step back, but the overall trend appears to be in the right direction.”

Africa’s strong economic growth adds to the case for long-term optimism. The McKinsey Global Institute’s Lions on the Move: The Progress and Potential of African Economies (2010) is one of two widely noted studies from the business world that draw attention to sub-Saharan Africa as the fastest-growing region in the world. Many critics of the thesis that economic growth and democracy go hand in hand point out that a strong economy can sometimes take the pressure off autocrats, as has been the case in Ethiopia and, of course, China. But the investment bank Renaissance Capital, in a study authored by its staff, The Fastest Billion: The Story Behind Africa’s Economic Revolution (2012), argues that growing investment in education, health, transportation infrastructure, and manufacturing is creating an atmosphere conducive to democracy. Poor, illiterate citizens are easy marks for autocrats; rising levels of income and education have already created an increasingly activist public that is putting pressure on governments to be responsive and transparent.

Charles Robertson, global chief economist at Renaissance Capital, writes that his company counts 31 African democracies today and expects to see more than a dozen new ones by 2050, “with just a few autocratic, energy-rich exporters left that are wealthy enough to buy off their middle class.” This year, he writes, “South Africa will join a few others such as Botswana and Mauritius above the key $10,000 per capita GDP level above which no democracy has ever died.”

Even if Robertson’s forecast is correct, the road to 2050 will not be easy. The conventional wisdom in the West is that if we put in place a constitutional framework and a body of laws and regulations, and get the structures and institutions of state right, then democracy will follow. But that view is grounded in the assumption that people in every country share a sense of national unity and connection. In Africa, that has not been the case until very recently. The 1884–85 Berlin Conference divided the continent into entities whose boundaries cut across ethnic, regional, religious, natural resource, and geographic lines. It created countries gripped by ethnic conflict and competition for resources, which, despite the beginnings of democratic culture in Africa, still poison many of these states.

Let’s not forget the example of Mali, which not very long ago was lauded as the paragon of democracy in Africa. A 1991 coup led to a new constitution and a democratic, multiparty state. The coup leader, Amadou Toumani Touré, won election as president in 2002, and the ensuing years brought free and fair elections and all the other trappings of constitutional democracy. What they did not bring was a government that dealt with the inequality of resource distribution, education, and opportunity, primarily for nomadic Tuareg tribesmen in the north, who felt culturally and politically marginalized by the dominant Mandé society of the south. The Tuareg were especially embittered by threats to their pastoralist way of life. Kept under control by the Malian military for years, these tribal groups surged back into rebellion after men and arms came pouring into the region from the war against Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. The Malian army, taking increasing losses, overthrew Touré early last year, and since then Al Qaeda and other Islamist extremist groups have exploited the instability to establish an Islamist stronghold in the north. Now it seems very likely that a multinational force will be assembled to drive the Islamists out.

True democracy depends on a set of underlying understandings, a sense of interdependence, a definition of a national community, or, in brief, a common “vision.” With my longtime colleague the late Howard Wolpe and others, I have spent years in Africa trying to build just such understandings. This means physically bringing together key leaders representing all ethnic, political, geographic, and religious groups to rebuild trust and ordinary communications that were lost in times of strife. This sort of contact helps engender the sense of interdependence without which they cannot collaborate on a sustained basis on the recovery, development, and democratization of their countries. Wolpe, who, among other accomplishments, served 14 years in the House of Representatives, chairing the subcommittee on Africa for a dozen of them, spoke with the wisdom of a political veteran. “You can’t expect an individual to feel any different about his competitor the day after an election than he did the day before,” he more than once reminded me. That says it all.

Democracy in Africa is fragile. Single parties still tend to dominate and backsliding is common. There will be more setbacks. But democracy has a new resilience and undeniable momentum. Last April, when Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade forced his way onto the ballot in a bid for a third term that the constitution seemed to forbid, Senegalese took to the streets in protest and the international community pushed back. Wade lost a runoff election in a landslide and was forced to accept the verdict of the people. This is emblematic of the new Africa.

Throughout Africa, the young, educated, and technology-savvy Africans who now make up the majority of the continent’s one billion people are demanding freedom. Economic opportunities, the free flow of outside investment capital, the move to drop intra-Africa barriers to trade and commerce, a globe united by technology, and many other forces mean that democracy’s future in Africa is about as safe as it can be. The four decades that I have spent witnessing this transition have been filled with excitement, sometimes danger and horror, frustration and anger, but in the end, inspiration and fulfillment as Africa takes its rightful place in the global village.