In 1998, on a staticky television in a small Oaxaca town, I watched Mexico’s most famous newscaster interview one of the country’s most famous criminals. Daniel Arizmendi López, known as El Mochaorejas—the “ear chopper”—had granted an interview to Televisa after his arrest. The bland discussion of his gruesome crimes repelled me, yet I could not turn away from Arizmendi’s flat stare. He had kidnapped dozens of people. Occasionally, he murdered them. More often, he severed a victim’s ear with poultry scissors and mailed it to the family. The practice had earned him millions in ransom payments, but finally it earned him a 50-year prison sentence. During a long surge in violent crime triggered by Mexico’s 1994 economic crisis, Arizmendi’s arrest came as a national relief, symbolizing some small degree of official control amid spiraling insecurity.

Now Mexico is entering the sixth year of an ever bloodier drug war. The country’s attorney general recently estimated that 48,000 people have been killed in drug-related violence since President Felipe Calderón declared war on the cartels in 2006. In this grisly maelstrom, growing devotion to Santa Muerte, Mexico’s folk saint of death, is understandable. A wide range of remedies are attributed to her intercession: vengeance, restored health, the acquisition of wealth, and healing for broken hearts.

When I watched Daniel Arizmendi shrug off his crimes in 1998, I had never heard of Saint Death. Much later, even after living in Mexico for several years, I still conflated Santa Muerte and La Calavera Catrina, the comical, proper-lady skeleton made famous a century ago by artist José Guadalupe Posada. Though “Saint Death” has been venerated at least as far back as colonial times, she’s far less public than most of Mexico’s pantheon of both church-sanctioned and folk saints.

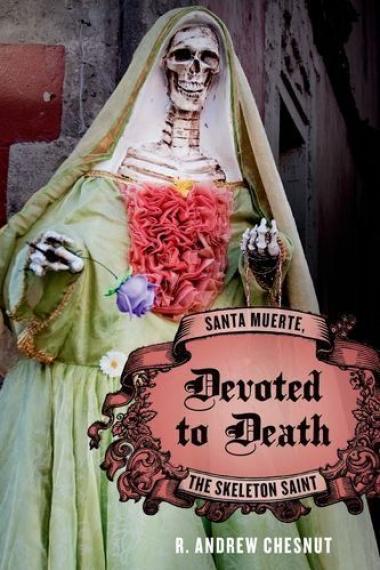

An early public devotee of Santa Muerte, Arizmendi earns multiple mentions in R. Andrew Chesnut’s Devoted to Death. Ever since Arizmendi’s high-profile arrest, Chesnut notes, journalists have focused on Saint Death’s vogue among drug traffickers and other criminals, while missing the larger story of a female folk saint (rejected by the Catholic Church) who has become nearly as popular as Mexico’s patron saint, the Virgin of Guadalupe.

The first book about Santa Muerte published in the United States, Devoted to Death offers readers a tour of Saint Death’s varied roles in Mexican pop culture and quotidian life. Chesnut traces her history to 18th-century colonial records, exploring her possible origins in the Grim Reaper of medieval Europe and the Aztec death goddess Mictecacihuatl. He describes briefly how the cult of Saint Death exemplifies the quintessentially Mexican syncretism of Catholicism, native cosmology, Old and New World pagan rituals, and Afro-Cuban Santería. Perhaps most compelling are his reviews of her colorful appearances in Mexican songs, films, television shows, and novels, and even the U.S. television drama series Breaking Bad and Dexter.

Chesnut, a scholar of Catholic and religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, provides fascinating glimpses into Saint Death devotional practices on both sides of the border. One Santa Muerte devotee Chesnut interviewed tells of hiding her “Bony Lady” statuettes in her purse and taking them to Mass, so that the priest might unknowingly bless them. Chesnut mentions that the leader of a temple in Los Angeles weds men to Saint Death for a six-month period of sexual abstinence and devotion, but does not describe the practice nor speak to anyone who has taken the vow. He does, however, document the deeply gendered dynamics of specific petitions made to Saint Death: Women frequently ask her to bring back wayward lovers or cure husbands of alcoholism, while men more often request protection from the authorities.

Though most of the critical attention given to Chesnut’s book has come from the Catholic press, it deserves wider readership among Mexico watchers of all religious persuasions. Santa Muerte’s popularity speaks volumes about contemporary life in Mexico amid the drug war’s unprecedented violence. Chesnut’s book is readable and accessible, if at times his tone is rather too casual. Like one of the Santa Muerte–inspired films the author describes—indeed, like the kidnapper and murderer who first brought Saint Death into the public eye—Devoted to Death “is engrossing in a pulp fiction kind of way.”