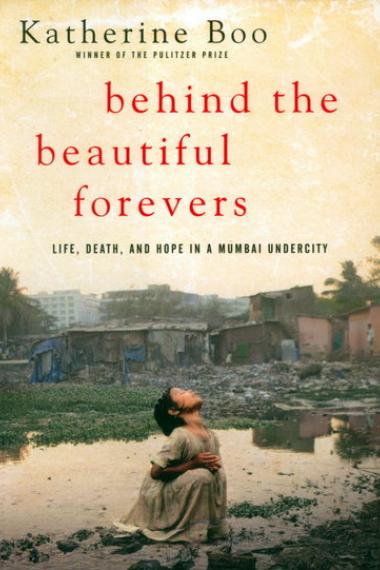

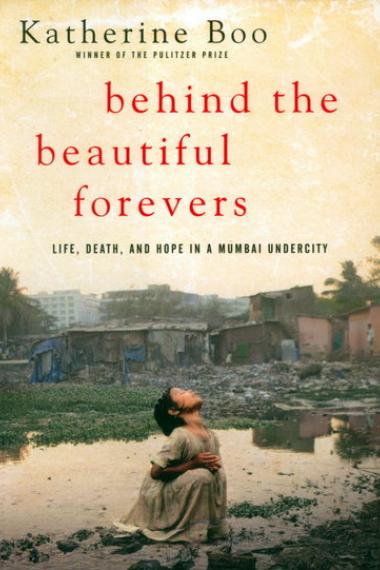

In Behind the Beautiful Forevers, a portrait of a slum in Mumbai, India, Katherine Boo sketches characters with Dickensian vividness against the black machinations of communal enmities, caste and ethnic politics, class prejudice, sexism, and corruption. Boo, whose long-form journalism on the American poor has earned her a Pulitzer Prize, a MacArthur Fellowship, and other awards, set herself a difficult task with this, her first book: to dramatize the effects of poverty and corruption on everything they touch. The poverty in Mumbai—indeed, in all the developing world’s megacities—can reinforce ties among neighbors; more often, it breeds suspicion, gangs, and lethal jealousies.

To illustrate her global concerns, Boo ratchets them down to events in a single community. It is 2008 in Annawadi, a Mumbai squatter settlement of 335 huts built next to an international airport. Palm trees, razor-wire fences, and glass towers of luxury hotels ring the slum. In a hut, a teenager named Abdul Husain is putting up a shelf on which his mother, Zehrunisa, can store her cooking supplies. On the other side of the wall where the shelf is to be mounted lives Fatima, or “One Leg,” a Hindu woman named for a congenital deformity that forced her into marriage with a sickly, elderly Muslim. Now she is a luridly made-up, indiscriminately promiscuous madwoman on crutches, with an irrational hatred of the more successful Husain family. Abdul’s taps against the wall send brick dust drifting into a pot of rice on Fatima’s stove, triggering a chain of events that will bring death to Fatima and economic ruin to the Husain family.

In the eyes of their city, all Annawadians are criminals, squatters on airport property, so they cannot open businesses. Most are trash sorters, selling metals and plastic they gather from random sources or buy from children who risk their lives nightly to pluck bits of the recyclables from a roadway. Some of the garbage, however, is obtained by trespassing on hotel grounds, or is stolen from construction sites. Whenever a family purchases a television set, improves its property, or sends a child to school, a policeman’s first suspicion is that the money must have come from some sort of illegality. The only way to avoid jail is to pay off the police, who share their take with judges and lawyers. It is a sordid game, its rules understood and played by all.

Of the slum’s 3,000 inhabitants, only six have full-time jobs, yet by government standards Annawadi does not fall below the poverty level. Most of the men and boys, including Abdul, his tubercular father, and Fatima’s TB-ridden husband, are model entrepreneurs, recyclers with an eye to the burgeoning Chinese metals market on the eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. It has been a memorable year for Indian trash sorters such as Abdul, leading, in his case, to new tiles on the floor and the in installation of the fatal cooking shelf. His father is too sick to work much, so Abdul is singlehandedly supporting his family on the equivalent of about $11 a day.

On the July day when brick dust ruins her rice, Fatima decides to trap the Husains by drawing them into a public brawl. An outdoor shouting match ensues, witnessed by all the neighbors. Zehrunisa calls Fatima a prostitute; Abdul, ever the conciliator, pulls them apart, and Fatima then takes a rickshaw directly to the police station, where she reports that the other woman has assaulted her. Within a few minutes, Zehrunisa arrives to contradict Fatima’s story, but too late. Fatima is sent home, her complaint largely ignored, but Zehrunisa is forced to stay, and the extortion process begins. The shakedown starts modestly at 1,000 rupees (about $20), to be given to Fatima—and shared, of course, with the policemen.

As Zehrunisa languishes in the police station, the Husains’ oldest daughter, Kehkashan, charges Fatima with the lies that landed her mother in custody, while hundreds of neighbors look on. Mr. Husain, who was out trying to buy floor tiles and missed the original encounter, now threatens to give Fatima a real beating.

I must intervene here, to point out one of many background details that leap off the page. Kehkashan has recently left her husband—a cousin whom her family arranged for her to marry when the two were toddlers—because she found pictures of another woman on his cell phone. The young, urban Indian underclass is not inexperienced in the ways of modern technology. Its members play video games and watch movies, but, like their peers in other megacities, they are not really part of the larger metropolis. Only arrests and detentions, albeit frequent, tend to take them out of Annawadi and its immediate environs. Still, all of them dream of leaving, and believe they will.

Back at her hut, Fatima plots her next move: She will set herself on fire, then quickly douse the flames with water and blame the Husains for trying to burn her. Once the plan is set in motion, though, she doesn’t extinguish the flames quickly enough. Carried to a hospital, she dies of an infection three days later. But a small, cruel, incomprehensible revolution has been launched. No one in authority believes that the Husains murdered Fatima, whose own young daughter witnessed the burning incident and told what she saw. Even so, without bribes or the intervention of higher-ranking authorities, corrupted justice marches on. The rest of the book traces its expanding implications.

Boo never underestimates the force of class jealousy. Arrests and jailings, especially of the relatively successful, are first-rate entertainment for the neighbors. Early on, Boo summarizes the view of Asha, a would-be slumlord and local power player who lives near the Husains: “She had by now seen past the obvious truth—that Mumbai was a hive of hope and ambition—to a profitable corollary. Mumbai was a place of festering grievance and ambient envy. Was there a soul in this enriching, unequal city who didn’t blame his dissatisfaction on someone else? . . . Everyone, everywhere, complained about their neighbors.” Asha understands the link between envy and corruption. It can be used. Others’ yearnings, exploited smartly, are openings to wealth and power. Asha’s perfect daughter, Manju, might—with luck—become Annawadi’s first college graduate.

If there’s hope, it lies with the children. Many are orphans, or effectively so, given the ravages of drink and tuberculosis, but they retain many of the charms of childhood: enthusiasm, knacks for mimicry and tale telling, and a readiness to act the daredevil. Many will fall to drug abuse, road accidents, and suicide. Arranged marriages, gang violence, preventable diseases, and incarceration will claim even the most hopeful. But they are true believers in the rising economic tide. Boo muses, “Annawadians now spoke of better lives casually, as if fortune were a cousin arriving on Sunday, as if the future would look nothing like the past.”

For opportunists such as Asha, Boo writes, that fortune can arrive in many forms. “In the West, and among some in the Indian elite, this word, corruption, had purely negative connotations; it was seen as blocking India’s modern, global ambitions. But for the poor of a country where corruption thieved a great deal of opportunity, corruption was one of the genuine opportunities that remained.” In other words, everyone on top is out to squeeze you. Not destroy you—they need their share of your services, often sexual, and great chunks of your income. With corruption the one constant underneath the narrative of a progressive and prosperous India, there’s no reason you can’t profit, as Asha does, from dalliances with police inspectors and politicians.

Everyone below you will scheme and lie, and, yes, try to destroy you, because the surest mark of success in Annawadi is to witness, or cause, a neighbor’s fall. Schadenfreude could have been an Annawadian invention. And the competition is not simply economic: If your children are in school and doing well, aspersions will be cast—who are you sleeping with? If you manage to fix up your hut, install a shelf, tile the floor, or buy a television set, you’ll attract the scorn of your neighbors—what did you steal? Conspicuous success will eventually earn police attention.

This has been an uncomfortable book to read, more so because I trust the reporting. Boo, whose husband is Indian, lived for several months in Annawadi over a three-year period. She does not speak the languages (Hindi, Urdu, and Marathi), but relied on translators and multiple interviews. The dynamics all ring true. An uncle of mine used to say, of the joint family, in which many generations of an Indian family live communally, “In times of stress, a fortress. Otherwise, a madhouse.” Those words convey the atmosphere of Annawadi, where the smallest incident can incite a riot, and an act of generosity can mend a rift.

Boo’s take on India and the people she obviously loves (in an exasperated way) shows that the country’s ancient social structures run more like the joint family than a class system. The great terror is not incarceration but exclusion, or, finally, banishment. The old caste-and-class conflicts are weakening—especially in the cities, where India’s future is being written—but they still trump the call to collective revolt against corrupt and arrogant overlords.

The future in Annawadi, even for the more privileged, is still unreadable. Boo’s last words in Behind the Beautiful Forevers are cautionary and apply universally: “If the house is crooked and crumbling, and the land on which it sits uneven, is it possible to make anything lie straight?”